Psychologist Kathleen Pike on How to Handle Your Mental Health at Work

July 05, 2019 | Filed in: Woman of the Week

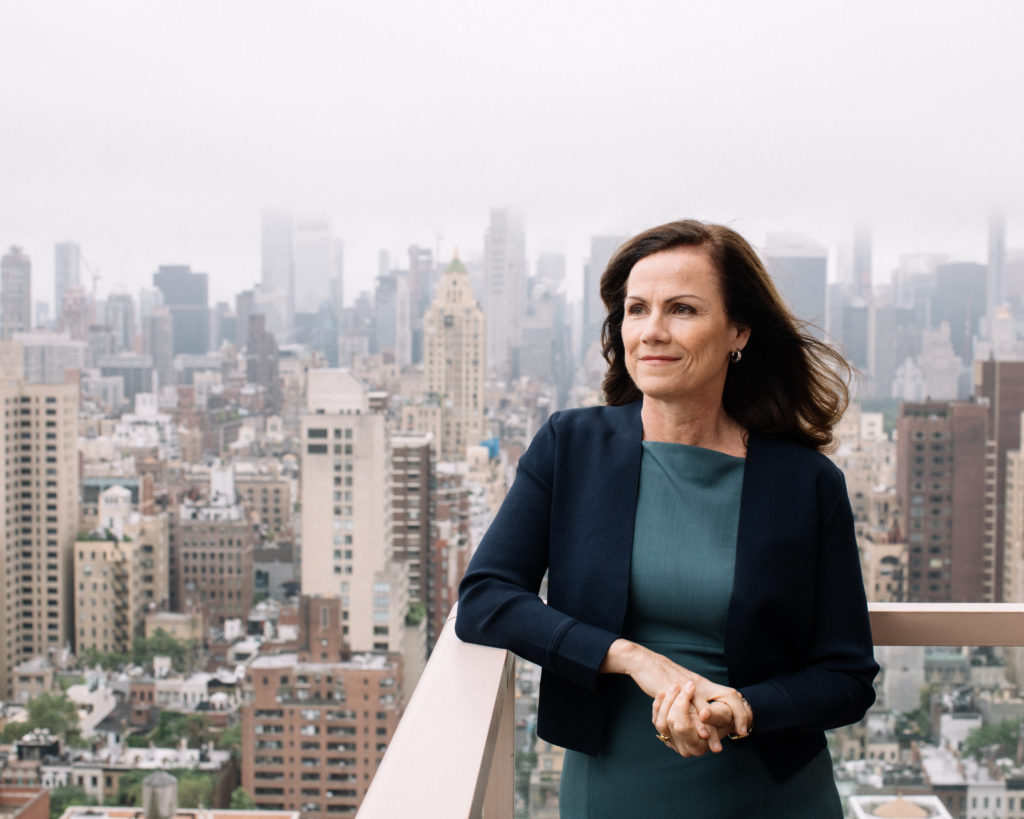

Kathleen Pike is a psychologist, professor at Columbia University, and the director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Capacity Building and Training in Global Mental Health. It’s a mouthful of a name, yes, and the goal of the program is pretty grand, too: to translate new psychology research into specific action plans to improve mental health internationally—not an easy job. We visited Kathleen at her Manhattan apartment, where she spoke with us about how she fortifies her own mental health reserves, her belief that work/life balance makes women feel badly about themselves, and why beekeeping is good for her brain.

Kathleen wears the Emily dress.

I THOUGHT I’D PURSUE A CAREER IN DIPLOMACY, so I studied international relations as an undergraduate. I wanted to understand how culture and society affect how people think. Eventually, that interest ran deeper, and I started to look at how certain social environments put us at risk for mental health problems, or protect us from them.

AFTER I FINISHED MY DOCTORATE IN PSYCHOLOGY, I went to Japan to look at cultural risk factors and eating disorders. My specific area of interest was trying to understand why eating disorders were more prominent in some societies than others. In that context, I wound up spending over 10 years in Japan. As I became more involved in understanding eating disorders, I also became more broadly interested in different ways of understanding mental health and mental illness in different cultures. That ultimately led me back to Columbia University, where I set up and now direct the Global Mental Health Program at Columbia University that has been designated a World Health Organization Collaborating Centre. Our focus is on sharing information and research around the world to advance global mental health.

Kathleen wears the Bergman top, the Pippa pant, and the Broadway belt.

AT THIS POINT, MENTAL ILLNESS IS THE LEADING CAUSE OF DISABILITY in the world. Yet it is also the most poorly funded component of health, compared to other major conditions like cancer, heart disease, or HIV and AIDS. My work is very focused on closing the gap between what we know and what we do. How do we put knowledge into practice? How do we get what we know into the hands, minds, and practices of people who maybe don’t think of themselves as mental health professionals, but who can have a significant impact on eliminating prejudice, discrimination, and stigma in promoting mental health and well-being?

MY STUDIES OF MENTAL HEALTH CERTAINLY INFORM how I want to live and work and play. It’s interesting how embedded the stigma against talking about mental health still is, though. I’ve grappled with it in my own personal life. A few years ago, I had an unanticipated trauma that left me reeling, and afterward I had a stretch of very real depression. As a clinical psychologist who runs a program in global mental health, I had access to therapy and care. But still, I didn’t tell anyone at work. Once I realized that I was keeping it to myself, I made a point of telling everybody at my office. It was a real “aha” experience for me, in terms of how unconscious and deeply entrenched the shame of depression can be. I think about it now whenever I talk to people about the importance of making it okay to talk about mental health.

Kathleen wears the Ashley dress, the Sant Ambroeus jardigan, and the Lyssa earrings.

IT’S UNIVERSALLY DIFFICULT TO TALK ABOUT MENTAL HEALTH because it involves a declaration of vulnerability. I try very hard to practice what I preach in terms of engaging in lifestyle choices that promote mental health, including exercise, sleep, social engagement, and having positive social supports. I work on building resilience and mental health reserves for the moments in my life that will be difficult. No matter how carefully we engage with the world, there will be moments when our mental health is challenged or threatened, just like other health conditions. It’s important to recognize that those moments will come, and that when they do, we will need interventions and additional supports in the same way that we do when we break an ankle.

THE INTENSITY OF THE DEPRESSION has passed, but I have continued in therapy. I see it as an opportunity for reflection and growth. I also safeguard my own mental reserves through several activities that are a big part of my life. I’m a recreational runner, and I find that it’s a really healthy and important part of managing my energy and mood. I also do ceramics as a hobby. Building things out of clay is actually a great metaphor for mental health. When you start creating a pot, you have an idea about what it will be, but it takes practice and work to make it. You need to shape it rapidly enough so that the clay doesn’t get dry and brittle, but not so rapidly that pieces come flying off. Then you put it in the kiln and hope that it all holds together. But sometimes, pieces crack.

Kathleen wears the Emily dress and the Ginger pump.

ANOTHER BIG PART OF MY MENTAL HEALTH IS BEEKEEPING. The lessons I have learned as a beekeeper are enormously applicable to the workforce. In a beehive, everyone has a job. The queen is really important, but she is only as good as her colony, because the queen bee makes no honey. She just lays the eggs. What it means for 65,000 bees to find resources, bring them back, and create something of value to the collective that sustains the life of each individual bee—it’s just a fascinating ecosystem. We keep our bees at our family beach house, and I give away the honey to friends and family.

A CERTAIN AMOUNT OF STRESS IS VERY USEFUL in terms of focusing and organizing your own resources. What’s critical, though, is learning when you’re on the dark side of that curve. The danger is when there’s too much stress, and each person has their own indicators for that. For me, I start to notice that I’m not sleeping as much. My right eye starts twitching. Those are indicators that I need to bring that pressure down.

Kathleen wears the Bergman top, the Pippa pant, the Broadway belt, the Lyssa earrings, and the Ginger pump.

I FREQUENTLY MENTOR YOUNG WOMEN IN MY FIELD, and I’ve noticed that there is a lot of rhetoric around work-life balance that’s designed to make people feel bad, particularly women. For example, men are excused much more quickly for missing a family event or being late because of a work engagement than women are. I tell my mentees that they should not plague themselves with the constant criticism of work-life balance because they will only achieve that balance for short periods of time at certain moments in their lives. It’s like sailing: Sometimes the winds take us exactly where we want to go, and we work the sails and enjoy that thrill. Then the winds die down or come from a different direction, and we struggle to get anywhere. We may have to take certain sails down until the situation changes. What we really want to do is become good at handling the sails and putting them up and taking them down. As long as we haven’t capsized, then we’re in a state of work-life balance! And you’re the captain of your ship.

TODAY, THERE’S AN EXPECTATION, ESPECIALLY among young professionals, that our lives need to be more integrated into our work. People feel a need to pursue careers that meet a wide range of criteria, including purpose, economic value, meaning, and status. That’s not a bad thing—in fact, it can be very good—but it puts an enormous amount of pressure on young professionals. That pressure is different from previous generations or other cultures. Those previous generations also worked hard, but they didn’t expect to get so much gratification or meaning out of their jobs, and found those things elsewhere instead. We have to build a new 21st-century model for work that doesn’t exist yet, so we’re in a time of flux, and that can be very stressful.

Kathleen wears the Ashley dress, the Sant Ambroeus jardigan, and the Lyssa earrings.

THERE’S A BIG OPPORTUNITY FOR CORPORATIONS at this moment to think systemically about how to promote the health and well-being of their employees and to really incorporate mental health and wellness in the performance indicators. If we look at economic models, in 1970 Milton Friedman wrote that the essential purpose of a business is to generate profit for shareholders. In that view, the workplace purpose is to maximize productivity. If we zoom out and look at economic productivity from a bigger, more existential perspective, its purpose is to increase the health and well-being of a population. But somehow, at some point, it flipped—health and well-being became in service of productivity, instead of productivity being in service of health and well-being. The endpoint is not economic productivity. The endpoint is a higher quality of life.

MAXIMIZING PRODUCTIVITY AT THE EXPENSE OF THE MENTAL HEALTH and well-being of our people and planet—that needs to be reckoned with. These questions are playing out not only in the workplace, but across society. How do we ensure that our organizational systems, our families, and our homes and our cities are designed in a way that supports the highest quality of life for the largest number of people?

Photographs by Rich Gilligan. Styling by Liz Young.