Anonymous Asks: Does Your Career Growth Have a Ceiling?

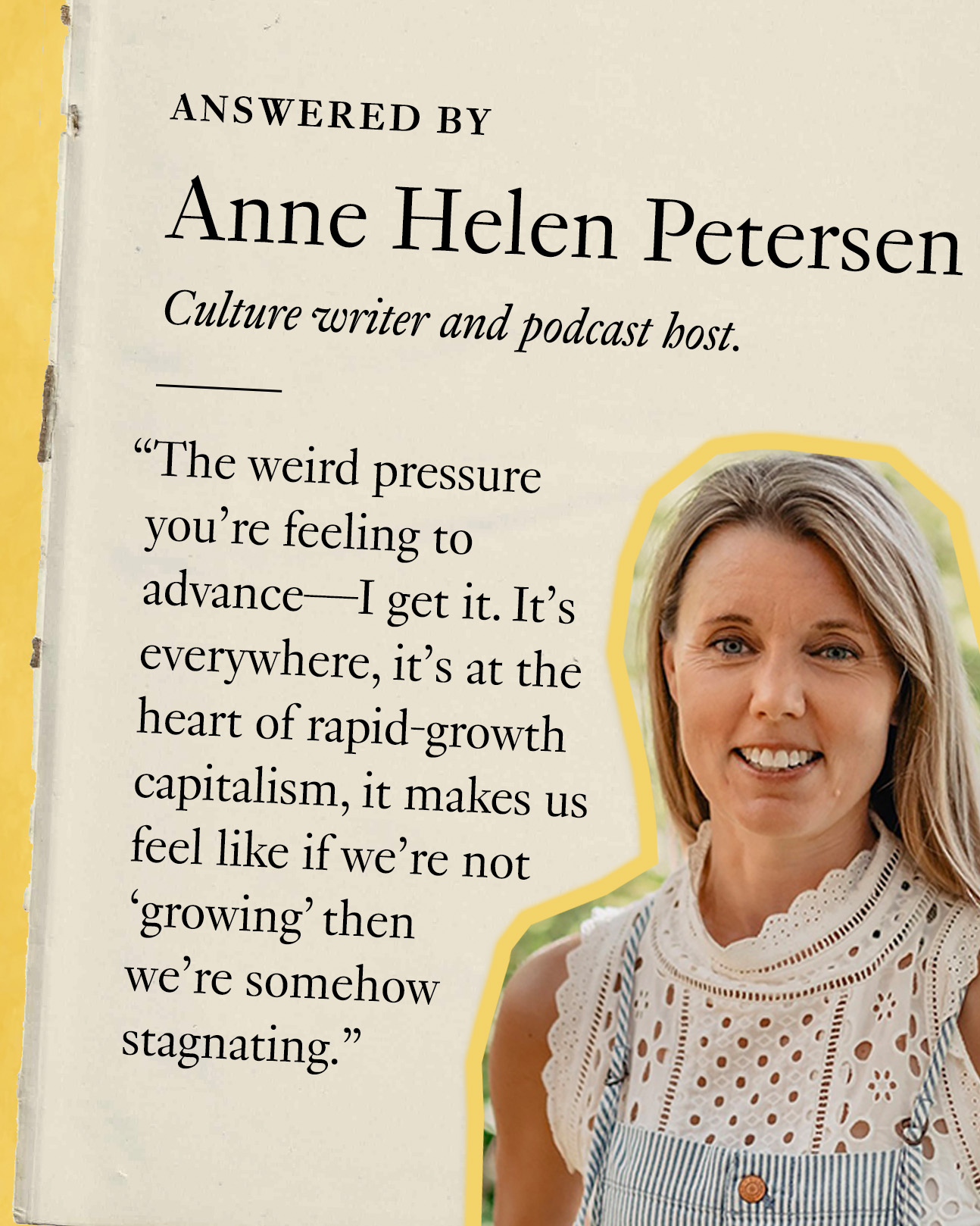

Culture writer and podcast host Anne Helen Petersen answers anonymous career questions from our community.

Want more M Dash?

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Thank you!

Anonymous:

I’m 40 and a senior manager at a nonprofit. I manage two employees, and I really dislike this aspect of my job, but I don’t see any advancement for myself at my company (or any other company) solely as an individual contributor—the only advancement in my career is to move into a director position, which would involve managing more people. Both pursuing a director position and staying at my current level feels bleak. Any advice on how to proceed? Is it appropriate to share with my manager that I don’t enjoy being in a leadership position? Are there any tips to mentally deal with the idea that I’ve reached the top of what I’ll achieve in my career and will be in the same position for the next 20 years?

Anne Helen Petersen:

I can’t tell you how many questions we’ve fielded (at my podcast, Work Appropriate) that are some version of this question. If you think about it, the problem is pretty foundational: most organizations have devalued management skills or eliminated positions whose primary role was, well, managing. Instead, they “add on” management as a task as you advance through the ranks. This strategy not only devalues good management (it’s an afterthought, if it’s thought of at all) but also puts a whole lot of people in management positions with no desire or aptitude for management. People, in other words, like you—who’ve realized that it’s the only way to make a bit more money, to advance within the company, and to keep their career from “stagnating.”

I’ve found this style of “add-on” management is particularly common at start-ups and nonprofits, both of which have pretty messed up org charts either out of negligence (“we’re too busy creating to think about the fact that we don’t have an HR department!”) or scarcity (not enough funding for all the work that needs to be done, so I guess a whole lot of people are going to do somewhere between 1.5 and 3 jobs in one). It ends up backing people into a corner, particularly people like you who’ve been in the workforce for nearly two decades and probably made some unconscious decisions a while ago about whether you were “leadership” material (gunning for the c-suite) or really liked your job fine, thanks.

Now, I want to acknowledge the weird pressure you’re feeling to advance—I get it. We all get it. It’s everywhere, it’s at the heart of rapid-growth capitalism, it makes us feel like if we’re not “growing” (in our jobs, in our fitness journeys, in our relationships, whatever) then we’re somehow stagnating. But figuring out what you’re good at and staying good at it is not going backwards. You’ll be able to refine skills and just be really f-ing competent at what you do. At some organizations, not moving up is a way to find yourself laid off—simply because organizations often cull “less valuable” (that’s BS, just so we’re clear) contributors with larger salaries who are readily replaceable by young people on the bottom of the salary rung. But that’s rarely the case at non-profits, and I’m guessing you already have a sense of whether or not it’s something you should be worried about.

What I’m hearing in your question is just a general dissatisfaction with your job—after all, if you stay, you still have to manage two people, which you dislike! And maybe you feel like you’ve really learned and contributed all you can learn and contribute in this role, and aren’t feeling even slightly challenged, and would feel invigorated by taking on something new. If that’s the case: put out some feelers. Looking at other jobs doesn’t mean taking them; sometimes it just means allowing yourself the thought experiment of taking them and seeing how your brain reacts. Maybe you make a lateral move (and still have to manage a person or two) but get to use your tools in new ways. Maybe that’s what will keep you re-investing in the work.

But if you’re only antsy because you feel like society says you should be advancing, that’s some work you can do internally and also with your organization. Have a frank conversation with your manager or leadership about how content you are in the job—but that your continued contentment stems, at least in part, from a lack of ambition to manage more people. If your manager has any empathy at all, they’ll get it. Lately I’ve found myself inspired by the work of Rainesford Stauffer, who’s been reexamining ambition—particularly the idea that it has to be our central motivator at work. Check out her book (or my interview with her), and have some frank conversations with yourself about what you want this next act of your working life to look like and whether or not that’s possible in your current workplace.

Anonymous:

After many rounds of interviews, I finally got the job. This would be my first time changing roles in almost a decade. Now, I need to decide if it’s the right decision for me and my family. Things I’m taking into consideration: is this a step to something I want? Am I ready to flex and learn new things? Can my family handle my new work-life balance, which would include a commute and no cell phone during the day?

Anne Helen Petersesn:

My answer to this one is to go back and think about why you were looking for a new job in the first place. Was it because of the pay? A toxic work environment? Because you were bored as hell? Something spurred you to apply for that job and then kept pushing you through the interview process. Sometimes, I think we apply for things simply to see if we can get them — and, as I mentioned above, to entertain the possibility of change. Personally, I think it’s a really useful exercise; even if you stay in your current position, it means that you’re choosing your choice, instead of just there because it’s your only option.

So now, it’s time to ask yourself: does this job actually offer what made me want to apply for it? Will that thing outweigh the temporary or long-term difficulties that accompany change? That’s your balance sheet. The one overarching piece of advice I have, though, is to consider if the thing that made you apply for a new job is your relation to work, broadly conceived, or your relationship to your particular position. If it’s your relationship to work, getting a new job won’t change that. The same problems and annoyances and difficulties will follow you. But if it’s your relationship to the specifics of a job, that’s a different story. And finally: if you don’t take the job, will you think of “what could’ve been” constantly? If you do take the job, are you going to pine for that old job? Try rolling out how you’ll feel if you say no—even practice typing the email. Does it feel like relief? Or a twinge of sadness? Something in you already knows what you want to do. Listen to it.